Part II

The Culmination of Another Morning Stalk

The Rifle

If you've perused the original "Part I" of this story you know that I had always intended to have a fine high grade English walnut stock made for this rifle, but lacked the time (and the funds) to do so. So, the original project focused on the mechanics, a new heavier barrel that was properly set up and an action tune for accuracy. I settled for an H S Precision sporter stock that I very much liked for along time, but at length I began to consider my original objective and in the interim my taste in rifles had evolved. In fact, at one point I nearly abandoned this rifle in favor of a Winchester or a Dakota (more on that in a moment), but I had so many experiences with it that I couldn't bring myself to part with it and resolved to fix the problems and make it into my ultimate heavy working rifle, but with classic style.

The thing that soured me on this rifle in its original form was the extractor. I had heard legends and rumors of bad Remington extractors and personally poo-pooed such folklore on occasion, but it finally happened to me. When you look at the Remington design its no wonder that it sometimes goes horribly wrong. The extractor is fixed, a mere sliver of metal at that, and the bolt face is larger than the base of the cartridge. This allows it to slip past the extractor for chambering. Reliable functioning depends on the ejector plunger to maintain the rim against the extractor, but there is enough room in the bolt face that for some rifles it just won't work consistently, reliably. Mine began to slip the rim early on. In fact, I had replaced the extractor just prior to going to Namibia in 2001. Its fortunate that it didn't act up when I was on safari. But it did act up and quite often in 2002. So much so, that I carried a short wooden dowel in my pack when I hunted in Colorado just in case I had to fling it down the bore and knock a case out of the chamber. The cases were never stuck tight, they were quite loose, but closing and opening the bolt did no good at all and I couldn't get my fingers in there and on the rim to flick them out. It was totally unacceptable.

My immediate thought was that I needed a Mauser style extractor like on a Dakota Model 76 or 97 or else one of the new Winchester Model 70 Classics, which restored the Pre-64 style extractor. However, for reasons already ennumerated, I decided to retain the Remington. Fortunately, it turns out that annoyed gunsmiths have long since solved this dilemma. The solution is to transform the Remington Model 700 bolt into a Post-64 Winchester bolt. That is impolite, but that is essentially what it amounts to. Its a giant leap forward over the stock Remington design and its not as far behind the beloved Mauser design as purists would have it. There are several conversions out there, I chose the kit by David Tubb. They are called Sako-style extractors, but they are equally similar to the Post-64 Winchester extractor. A slot has to be machined on the bolt, into which fits a spring loaded extractor that is always held against the cartridge rim. It works flawlessly now. I won't comment on the irony that I had to go to this effort to make the Remington as good as the long reviled Post-64 Winchester.

Closeup of New Tubb Sako-Style Extractor

Other changes were aesthetic in nature, but also tended to transform this Remington into a Winchester (sorry Big Green!). Let's face it, the Pre-64 Winchester Model 70 is the rifle by which all other rifles are judged and frankly even Winchester has lost the bubble on that one, more than once. I replaced the tacky aluminum alloy bottom metal. I also decided that I wanted a proper 3-position safety with a positive bolt lock and more dependability in blocking the trigger (another item for which I have heard rumors of dangerous unreliability, but blessedly never experienced myself). Lastly, that factory dog leg bolt handle ceased to find favor in my eyes. The first solution implemented was a Dakota replacement handle, but it was too wimpy looking on this big rifle (and was welded on such that it wouldn't clear the scope anyway), so I had Darrell Holland (Holland's Gunsmithing) weld on one of his long Pre-64 style handles. I also decided that I don't need a high power scope with a huge objective lens in order to hunt, even at long range. The longest shot that I ever took was with my old scope on 4X, the lowest setting; I was so caught up in the moment that it never occurred to me to change the magnification setting.

Here's the list of changes that were made to the rifle:

- David Tubb Sako-style extractor to replace the unreliable Remington factory extractor

- David Gentry 3-position safety installed

- Dakota classic-styled steel trigger guard and floorplate

- New England Custom Gun 2-leaf express rear island sight and front ramp

- Darrell Holland Pre-64 Model 70 style tactical bolt handle welded on

- Complete re-blue of the action and barrel

- Replace Leupold 4-12X Vari-X II with a Leupold 2.5-8X VX-III with Leupold bases & rings

Closeup of New Gentry 3-Position Safety and Holland Bolt Handle

Not to be overlooked was the stock, the main feature that began this exercise in refurbishment and transformation. I had Fred Zeglin commission me a classic style stock, with a long open wrist and straight round forearm. I got a really great English walnut blank from Dressel's (Paul & Sharon Dressel). The finished stock wears a Talley grip cap and swivel bases and is reinforced behind the recoil lug with a Talley crossbolt. It has the trim feel and handling characteristics of the H S Precision stock, but finally the aesthetics of a fine rifle.

It took nearly three years to complete the transformation, from the time I shipped it off to Zeglin in December of 2004 until I got it back in mid-2007 and then sent it off to Holland's, but at long last it was done in the autumn of 2007. The only remaining original factory parts are the receiver and trigger, but in my mind its the same rifle. Sort of like Granddad's old hatchet... What started out in 1993 as a poor man's Weatherby with a $100 rechambering of a stock Model 700 BDL ended up as a high end custom rifle some 14 years later. You could have bought a new Dakota or a Safari Express from the Winchester Custom Shop for what I have put into this rifle over the years, but its uniquely my creation and the tale of its journey adds to its appeal.

Right Profile View of the Finished Rifle

Left Profile View of the Finished Rifle

The Hunt

As far as hunting, 2007 had been a disaster. For all of 2007 and the first half of 2008 I didn't have time to think because of my work and only managed a single afternoon in the woods with a rifle in my hand. I was determined that 2008 would be different and I wanted to go on a major hunt again. I hadn't been since 2005 when hunted mule deer in Nebraska and that was rather anticlimactic, if successful, as it ended within the first hour or so on the first day of the hunt. It was also a ranch hunt, not a remote wilderness area. In 2006, Steve and I had flown up to Maine and driven two hours beyond a paved road into logging country to hunt northwoods whitetails and while a fun and relatively inexpensive hunt, it was fruitless. I sought adventure and Alaska came immediately to mind. However, by the time I was able to consider the possibility of commiting to a hunt in 2008 it was late in the year, I had missed most of the deadlines for tags and I had to realistically admit that few opportunities remained. Nevertheless, I was in luck. In early August I discovered a cancellation on a two-person hunt in the western Arctic region of Alaska offered by Cabela's and I jumped.

Unlike our first foray into the Last Frontier, this was to be a guided hunt, outfitted by Brad Saalsaa of Alaska Wilderness Charters and Guiding, Inc.. Its a similar arrangement to that we used in 1999 and 2004, except that a guide remains with the two hunters, sets up camp, cooks meals and cares for the carcass and trophy. I remembered well the effort required to haul a caribou carcass back to camp and welcomed the help.

I flew into Anchorage and spent the night, then caught a very early morning flight to Kotzebue, the largest Eskimo village in Alaska. Situated right on the Arctic Circle on the western coast of Alaska, its also a major staging area for Arctic industrial operations. Alaska Air flies 737s in and out of there several times a day and it has a deep water port on the Kotzebue Sound. That said, Kotzebue is not exactly Metropolis. Amenities are few and expensive, for obvious reasons.

Since this was a cancellation hunt I was to be partnered with a stranger. While I had misgivings about that, it was one of the concessions I had been ready to make in order to get to hunt this year. I had never met or spoken to my hunting partner for this trip prior to my arrival in Kotzebue, but Jason turned out to be as cheerful and good-natured a fellow hunter as one could want.

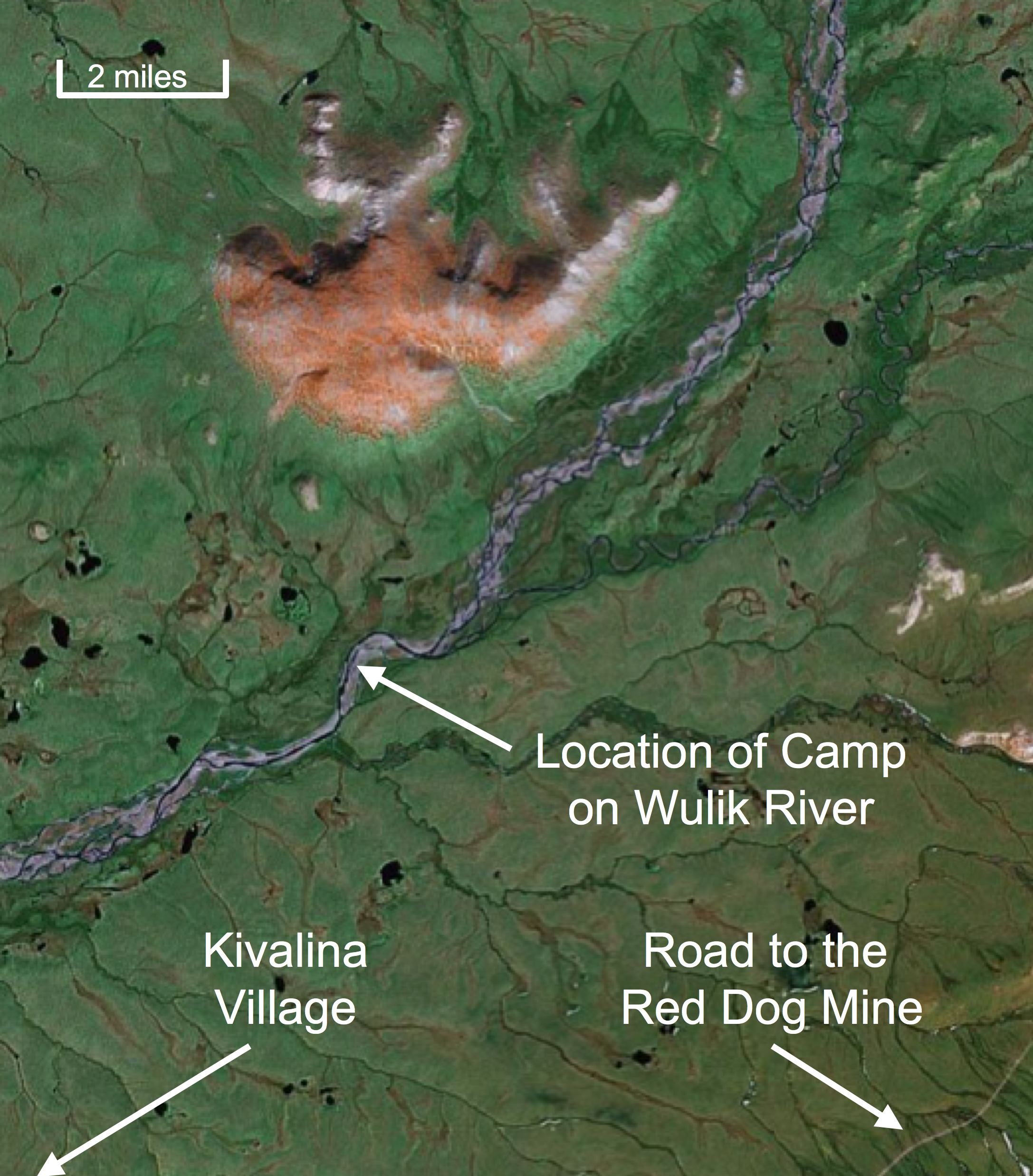

We left Kotzebue the same morning that I came in and flew about 60 miles north-northwest to a point a few miles inland from the Bering Sea on the Wulik River, not far from the village of Kivalina and the Red Dog mine. The planes landed on a gravel bar in a bend of the river. It was a great spot, with easy access to good water, out of the wind and a short walk to a good rise for surveillance of the surrounding terrain.

Map of the Location of Our Wulik River Camp

I had been disconcerted in our flight out by the dearth of caribou on the ground 2000 feet below as we flew over. I never saw a single caribou until we finally saw a small group near the Wulik River, but it contained no mature bulls. This Western Arctic herd had been described as numbering in the range of half a million animals by Cabela's Outdoor Adventures, however Brad Saalsaa had asserted that you would never see streams of hundreds of caribou as with the Mulchatna herd in the Alaskan Peninsula where I had previously hunted. Typically, it would be small groups of 10 or 20. That did not really bother me. I like to hunt. But there has to be game in the area and I was somewhat worried. Still, caribou can cover many miles in a day and I have experienced a landscape devoid of them as far as the eye can see on one day and the terrain thick as Alaskan mosquitos with them on the following day.

The Bush Plane Departs from Our Wulik River Camp

A Little Fishing First

Prior to our departure Brad Saalsaa had prudently suggested that we buy fishing licenses and provided us with rods, reels and some lures. The reason being that one can't hunt on the same day one flies in Alaska, so we'd need some alternative occupation. It turned out to be a fortuitous suggestion in several respects. For one thing, this specific location is world class for Arctic char and you can also catch grayling, Dolly Varden trout and chum salmon. I had wanted to fish for Arctic char in 2001 as part of the originally planned hunt in Labrador that evolved into the abortive hunt in Newfoundland, so this was an unexpected and very welcome development.

The Wulik River at this season is a shallow stream, scarcely 40 or 50 feet across at its widest and no more than waist deep in the holes. You could easily wade across in hip waders, although the current was strong in places and the rocks quite slippery, so I never attempted that feat. The water was bitter cold and I had no interest in a bath. It was amazing to me how many fish, and big fish, were packed into so small a stream. I used a brass spoon lure and they wore it out. Char are ferocious fighters and made great sport. We released almost all of them, but kept a few for eating, which proved to be the second fortuitous aspect of the fishing. Char are delicious. The flesh is something between salmon and trout. It looks rather like salmon, but is a little paler in color, about like cantaloupe. Our guide feasted us like kings on pan fried char steaks seasoned lightly with some blend of spices that he had packed along.

I Catch My First Arctic Char

While I didn't catch nearly as many fish as Jason, I did manage to catch the big one. There was a deep pool just behind a rocky bit of rapids and I had noted some big splashes coming from it. When he took the lure I knew that this fish was different. Less vigorous than the smaller char, he was nonetheless a lot stronger and I had to adjust the drag on my reel for fear of losing him. It was a batttle to land him on the light gear and I really enjoyed it. I believe its made a stream fisherman of me. I didn't have a scale, but I reckon that he weighed about 11 or 12 lbs. Apparently, they grow to twice that size. I can only imagine what that would be like.

The Big One!

The Stalk

On the first morning of the hunt the weather was not too cold under an overcast sky. We crossed a small feeder stream south of our camp and climbed the river embankment to look for game. We had not gotten to the highest ground when we were suddenly surprised by a group of a dozen-odd caribou that crested the rise and began to move across the hillside in front of us. We dropped. These were only cows and calves, but ordinarily you find the bulls bringing up the rear, often separated by some distance. The group finally sensed us and turned back, but when a dominant cow came up from behind they became confused and went back and forth. We waited. At length they migrated off to the East, moving more or less upriver.

We had not moved from this position when a second group drifted along in the tracks of the first group. This was getting good, especially since the bulls, when they finally appeared, would almost certainly move across broadside at a range of barely 200 yards.

However, that is not the way it happened. Instead, the group of bulls rose suddenly about 300 yards away to our right. I saw them out of the corner of my eye and signaled our guide. We studied them intently, judging antler growth and body size. There were two that looked to be good bulls, but one had a weak growth of the palm top on the right side, probably due to damage in velvet. I asked our guide, Jim Wehinger, what he thought and he judged that the one was not bad, but not a big bull by Boone and Crockett standards. That was enough to discourage my partner. I knew that it was significantly more impressive than the one I shot in 1999 and that was my sole criterion. I told him I wanted to make a try for it.

They appeared to be moving in a line that would take them directly on top of us. Hardly ideal. Fortunately, at that moment, and before any of them got wise to our presence, they decided to bed down and take a nap. Perfect, right? Well, the difficulty was that I did not have a shot.

Having bedded down, they were fully obscured by the rise. Additionally, the terrain was flat and devoid of anything that could be used as cover to make my approach. Basically, I'd have to slip up until I got a clear shot and pray that I got into such a position before the sharp-eyed young bull at the front of their group spotted me - and he wasn't napping. I decided that there was too much ground between us and that I had all kinds of time, so I began to low crawl across the tundra like a lizard. If you've never done that over uneven ground for a hundred yards, let me tell you that its tiring. I got hot and winded, which wouldn't improve my shooting.

Having closed the distance to 200 yards, I was advised by Jim to just stand up and walk right at them. I am not that confident in my standing shooting skill, particularly when winded, so I took a modified form of his counsel. Moving in a low crouch, I slipped with painful slowness closer, until I got within about 150 yards. Another difficulty was that a different bull had bedded in such a way that if they were suddenly roused, he would stand and block my shot. Between their fidgeting about and my flanking, I managed to overcome that problem. Finally, the young bull was alerted. The others began to rise, but the big bull stood up facing away from me and was unaware of the cause of the rousing. I dropped down, propped my elbows on my knees and shot him from behind the left ribs angling toward the offside shoulder. The 225 grain Trophy Bonded Bear Claw, one from a box of Federal Premiums I bought for our safari in Namibia in 2001, destroyed the lungs, passing close by the spine, and he simply collapsed without stirring. Incidentally, in the photo below the purple stains on my legs are from tundra blueberries.

The Mighty Bull is Felled

Me, Posing with My Hunting Partner Jason

Jim Wehinger is one of the toughest men I have ever encountered. He wore stocking foot waders every day, despite the fact that they froze every night. He could walk across that ankle wrenching tundra grass better than anyone I've ever seen. He seemed to be indifferent to cold that I found to be uncomfortable. He also packed out that caribou carcass in a single trip, less only the cape and antlers which I carried, refusing any suggestion of sharing the load. A retired sherriff's deputy, he spends half the year primarily hunting bears, which is a lot more physically challenging activity than hunting caribou.

Our Hunting Guide, Jim Wehinger, Glassing the Terrain

I am glad that I shot this bull, doubly glad that I did not defer from shooting on the morning of my first day, holding out for that big 400-class Boone and Crockett trophy. We continued to glass for bulls for Jason for the next five days, but never saw another one. Jason stayed a day after I flew out, but I don't think he had any success. I did not see any caribou on the 60 mile flight back to Kotzebue. The outfitter did a fine job with the equipment and provisions. Jim was a good guide and worked very hard. But the siting of the hunting camp, while logistically favorable, was a bad one. There simply was little to no opportunity for success and there were at least two other camps of hunters within a couple of miles. The air charter is a separate operation and the outfitter is reliant to some extent on their recommendation for camp location. Whatever the reason, that bull on the first morning was literally the only chance we had. Hunting the Western Arctic in Alaska for caribou is great sport, but with a herd as widely distributed as it is, in a territory as vast as this, its crucial that the camp be sited within a mile or two of reasonable concentrations of game and terrain permitting wide surveillance of the surroundings.

The Alaskan Arctic Tundra Landscape on a Frosty September Morning

Copyright 2008 - 2013 -- All Rights Reserved